The will of the people of Shizuoka Prefecture became clear in the gubernatorial election

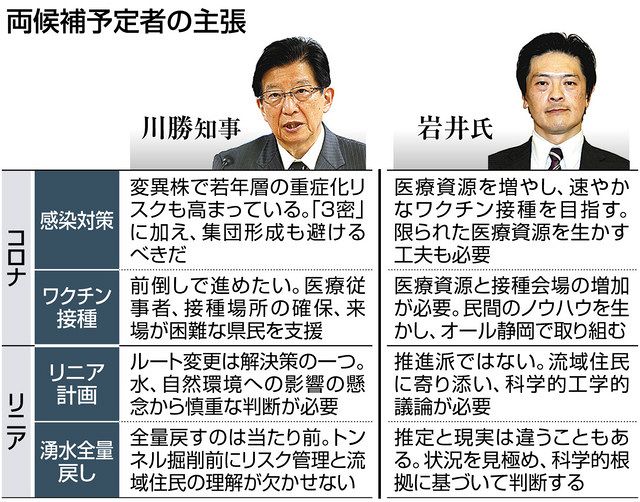

The biggest issue in the construction of the Central Linear Railway Shinkansen by JR Tokai is the understanding and cooperation of Shizuoka Prefecture. In June, Heita Kawakatsu was elected governor of the prefecture, and his policy of not granting construction permits for the section of the line that runs through the prefecture was supported by the people of the prefecture. So let's try to sort out what the issues are between JR Tokai and Shizuoka Prefecture and find a solution.

The Central Japan Railway's track length is 285.6 km between Shinagawa and Nagoya. Of the 285.6 km, 10.7 km of it will pass through Shizuoka Prefecture in the 25.0 km-long Minami-Alps Tunnel.

{...]

The Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism has approved the construction of the Linear Central Shinkansen, so JR Tokai can ignore the wishes of Shizuoka Prefecture and proceed with construction. However, Akihiro Ota, the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism at the time, required "understanding and cooperation of the local community through careful explanations to local residents" and "safe and reliable construction of the Minami-Alps Tunnel and other tunnels" when approving the project. In other words, the understanding and cooperation of the governor of Shizuoka Prefecture, who represents the local residents, is required.

In addition, under the River Law, the construction of the Linear Central Shinkansen cannot be approved without the Governor of Shizuoka Prefecture. This is because the facilities that use riverbed land for which permission is required include railroad tunnels, and the Minami-Alps Tunnel runs under the Oi River. Although the Oigawa River is a first class river managed by the national government, Shizuoka Prefecture has been entrusted with some of the authority by the national government.

What are the points of contention between JR Tokai and Shizuoka Prefecture?

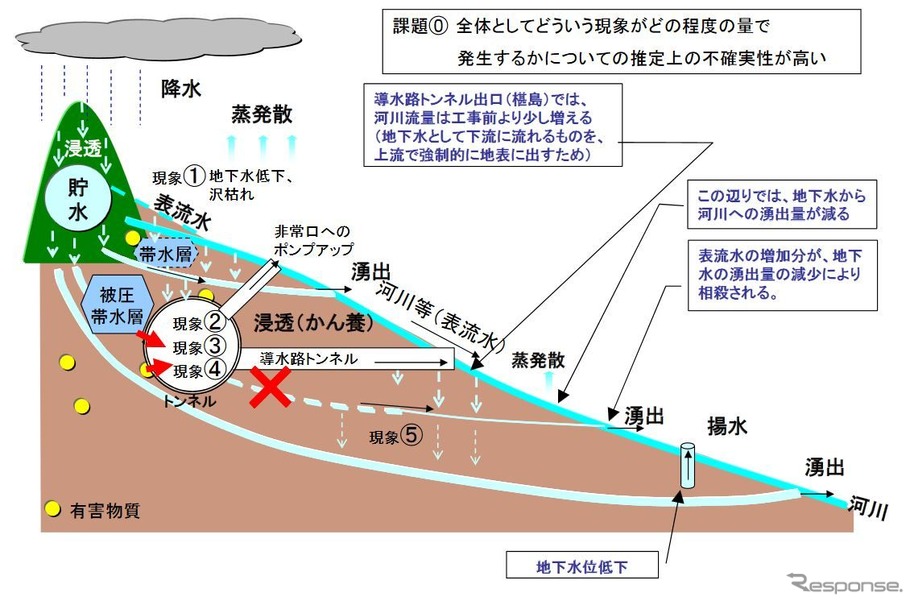

The main point of disagreement between JR Tokai and Shizuoka Prefecture is the Oi River. Let me briefly state the points of contention between the two sides. How much water will be lost from the Oi River due to the construction of the Minami-Alps Tunnel, and how will that water be replaced?

The groundwater in the Southern Alps, which was originally supposed to flow into the Oi River, will become spring water in the tunnel as a result of digging the Minami-Alps Tunnel. With today's civil engineering technology, no matter how sturdy the tunnel is made of concrete, it is impossible to completely prevent the water from flowing out.

JR Tokai estimates that the average volume of spring water in the Shizuoka Prefecture section of the Minami-Alps Tunnel is 2.67 cubic meters per second. On the other hand, the amount of water flowing into the Oi River, which will be reduced by the construction of the tunnel, is predicted to average about 2 cubic meters per second, from 11.9 cubic meters before construction to 9.87 cubic meters at the Tokusa weir of the Akaishi Power Plant upstream. It should be noted that these estimates were based on the assumption that the tunnel would not be concreted, which is unlikely to be the case in reality, so the volume of spring water is expected to decrease. In reality, this is not possible, so the amount of spring water is expected to decrease. However, JR Tokai has not announced how much this amount will be.

On September 7, 2021, the statement "JR Tokai estimates that the volume of spring water in the entire South Alps Tunnel averages 2.67 cubic meters per second" was revised to "JR Tokai estimates that the volume of spring water in the Shizuoka Prefecture section of the South Alps Tunnel.

In response, Shizuoka Prefecture argues that there is no scientific basis for the figures released by JR Tokai. Although they are highly accurate, they are still estimates, and the changes in the amount of water flowing into the Oi River that the tunnel will cause will not be determined until it is completed. While Shizuoka Prefecture's argument is understandable, many people will be surprised to learn that they have stumbled at this stage.

Assuming that the amount of water flowing into the tunnel is correct, the average of 2.67 cubic meters per second of water flowing into the tunnel in Shizuoka Prefecture will flow to the east side of the tunnel (Yamanashi Prefecture) and to the west side of the tunnel (Nagano Prefecture). The problem can be solved by diverting an average of about 2 cubic meters per second of the spring water that reaches the tunnel entrances to the Oi River. However, the entrance and exit of the Minami-Alps Tunnel is far from the Oi River on both the east and west sides, making it impossible to realize.

September 7, 2021: "Spring water in the tunnel that is estimated to average 2.67 cubic meters per second" has been corrected to "Spring water in the tunnel that is estimated to average 2.67 cubic meters per second in the section in Shizuoka Prefecture.

Therefore, JR Tokai announced that they would use a different method to return the water from the Oi River that will be lost due to the construction of the Minami-Alps Tunnel. From a point in Shizuoka Prefecture in the Minami-Alps Tunnel, which runs from the Yamanashi Prefecture side in a west-northwest direction, to Sawarajima in the Oi River basin, first in an east-southeast direction and then in a south-southeast direction, an 11.5-km-long conduit tunnel will be dug to discharge the spring water into the Oi River. Sawarajima is located about 2 km downstream from the Akaishi Power Plant's Kisai weir. The total volume of the spring water, including that pumped into the conduit tunnel and that pumped into the conduit, is estimated to be an average of 2.67 cubic meters per second.

[...]

Although Shizuoka Prefecture appreciates the water conduit, they question it, citing what will be done with the reduced amount of flowing water upstream of Sawarajima, and even downstream of that, the amount of groundwater appearing on the surface will be reduced, which will ultimately reduce the amount of flowing water in the Oi River. However, the difference in elevation between the South Alps Tunnel and Sawarajima is 12 meters, and if the outlet of the conduit is placed upstream of Sawarajima, the difference in elevation will be less, and there is a high possibility that water will not flow.

Shizuoka Prefecture, in response to JR Tokai's claim that 2.67 cubic meters per second of water will be returned, "demanded that the entire amount of (tunnel spring water) be returned to the Oigawa River permanently and without fail" (First Linear Central Shinkansen Shizuoka Construction Area Expert Meeting, "Handout 1-2: Main Background of the Oigawa River Water Resources Issue," April 27, 2020, page 1/3). It is claimed that It seems that they are just saying the same thing with different expressions, so there is no discrepancy between their arguments. However, in my interpretation, there are glimpses that Shizuoka Prefecture sometimes refers to the "tunnel" not as the section in Shizuoka Prefecture, but as the entire section in Yamanashi and Nagano Prefectures. It seems unlikely that the two sides will be able to come to an agreement.

In addition, Shizuoka Prefecture is insisting that the entire volume of spring water generated in the Minami-Alps Tunnel, or 2.67 cubic meters, be returned, rather than the average of 2.35 cubic meters per second. (The 1st Linear Central Shinkansen Shizuoka Construction Area Expert Meeting, "Handout 1-2: Main Background of the Oigawa River Water Resources Issue," April 27, 2020, page 1/3). It seems that they are just saying the same thing with different expressions, so there is no discrepancy between their arguments. However, in my interpretation, there are glimpses of the claim that Shizuoka Prefecture sometimes expands the scope of "tunnel" to include all sections of Yamanashi and Nagano prefectures, instead of the section in Shizuoka Prefecture in the Minami-Alps Tunnel.

There are parts of the project that do not meet Shizuoka Prefecture's demands in terms of safety.

To cite a few more, Shizuoka Prefecture has asked JR Tokai that the flow of water in the Oi River should not be reduced even while the Minami-Alps Tunnel is being dug, and although JR Tokai initially showed its willingness to comply with Shizuoka Prefecture's request, after an investigation it replied that it was not possible, mainly for safety reasons.

In order to meet Shizuoka Prefecture's request, the 25.0km-long Minami-Alps Tunnel would have to be bored from the middle section in Shizuoka Prefecture. This is because if the tunnel is dug from the Yamanashi side, close to the entrance and exit of the fault zone where a large amount of groundwater is believed to exist on the border between Shizuoka Prefecture and its eastern neighbor Yamanashi Prefecture, the spring water will not flow into the Oi River.

You may think it is impossible to dig a tunnel from the middle of a mountain, but theoretically it is possible. In order to dig the Minami-Alps Tunnel, a steeply sloping tunnel called the Sengoku Leaning Pit is being constructed from a higher place than the Minami-Alps Tunnel to reach a section in Shizuoka Prefecture. The Sengoku shaft will provide an additional work area for the construction of the tunnel and will also serve as an evacuation route once completed. Shizuoka Prefecture's hopes would be fulfilled if the tunnel could be bored through this inclined shaft into the fault zone at the prefectural border and the spring water could be channeled into a water conduit.

However, it is a downhill slope from the Sengoku shaft to the prefectural border fault zone, so even if a larger-than-expected volume of spring water is generated when the fault zone is reached, it will not flow behind the work site, and there is a limit to the amount of water that can be drained by pumps. The amount of water that can be drained by pumps is also limited. If this were to happen, the work site would be submerged and the workers would be in mortal danger. These are the reasons for safety. Shizuoka Prefecture seems to have understood the situation, but it does not seem to have dropped its original argument.

Despite Shizuoka Prefecture's claims, as of this moment, spring water from the Minami-Alps Tunnel construction in Yamanashi Prefecture is still flowing into the entrance on the Yamanashi side, and spring water from Nagano Prefecture is still flowing into the entrance on the Nagano side. The reason for this is that construction is already underway at the east and west entrances of the tunnel to create an advanced tunnel to drain the spring water and increase the working area of the main shaft through which trains pass.

Despite Shizuoka Prefecture's claims to the contrary, at this point the spring water generated by the Minami-Alps Tunnel construction is still flowing into Yamanashi and Nagano Prefectures. Despite Shizuoka Prefecture's claim, even at this point in time, spring water from the Minami-Alps Tunnel construction in Yamanashi Prefecture is flowing into the entrance on the Yamanashi Prefecture side, and spring water in Nagano Prefecture is flowing into the entrance on the Nagano Prefecture side.

The amount of spring water expected to flow to the entrances and exits on both Yamanashi and Nagano prefectures when the Minami-Alps Tunnel is completed is shown in "8-2-4 Water Environment - Water Resources for both Yamanashi and Nagano Prefectures in the Central Shinkansen (between Tokyo and Nagoya City) Environmental Impact Assessment (August 2014)" by JR Tokai. According to the "Water Environment - Water Resources," the maximum average water flow rate is 0.17 cubic meters per second in the Kawachi River (midstream) in the Tashiro River No. 1 Power Plant, south of the entrance and exit on the Yamanashi Prefecture side (including spring water from the No. 4 Minamikoma Tunnel just east of the Minami-Alps Tunnel), and 0.004 cubic meters per second in Tokorozawa (near the Kamazawa water source), east of the entrance and exit on the Nagano Prefecture side. The Oigawa River is also said to have a maximum average of 1.9 cubic meters per second on the Yamanashi side (Tashiro River No. 2 Power Plant, Oigawa River). Although the location of the spring is unknown, it must still be there at the present time, as the tunnel is being dug parallel to the main shaft through which trains pass, and an advanced shaft is being dug to drain the spring water, increase work space, and serve as an evacuation route once completed. Shizuoka Prefecture may want to point this out, but since the construction has been approved by other prefectures, they cannot interfere.

The amount of spring water that is expected to flow to the entrances and exits of both Yamanashi and Nagano prefectures upon completion of the Minami-Alps Tunnel is estimated to be about 0.31 cubic meters per second on average at the Yamanashi entrance and 0.01 cubic meters per second at the Nagano entrance, according to JR Tokai. According to the "Central Shinkansen (Tokyo-Nagoya City) Environmental Impact Assessment (August 2014), Yamanashi and Nagano Prefectures, 8-2-4 Water Environment - Water Resources" of the Central Japan Railway Company, the volume of spring water expected to flow to the entrances and exits of both Yamanashi and Nagano Prefectures upon completion of the Minami-Alps Tunnel is estimated to be a maximum of 0.17 cubic meters per second on average at the Kawachi River (midstream) in the Tashiro River No. 1 Power Plant, south of the Yamanashi Prefecture entrance (0.01 cubic meters per second on average at the No. 4 Power Plant, just east of the Minami-Alps Tunnel). Oigawa River) on the Yamanashi Prefecture side, and 1.9 cubic meters per second on the Tashiro River No. 2 Power Plant Oigawa River on the Yamanashi Prefecture side. According to JR Tokai, no spring water has been found during the construction of the Minami-Alps Tunnel in Yamanashi and Nagano prefectures.

The disagreement is still big. Is there a solution?

Shizuoka Prefecture is in favor of the construction of the linear central Shinkansen itself. That being the case, JR Tokai must prepare an answer that Shizuoka Prefecture can accept regarding the impact on the Oi River. However, it is true that the amount of water flowing in the Oi River will not be known until the tunnel is actually completed. Moreover, the disagreement over the amount of water that will decrease during the construction of the tunnel has been going around in circles, and there is no prospect of a solution.

So what should be done? I would like to propose the application of a method that has been used in real-life Shinkansen tunnels. The idea is to let the spring water in the tunnel flow from the roadbed, which is the tunnel floor, into the mountains.

Specifically, the roadbed, which is the foundation of the railroad track, would be lined with hydraulic slag, a material that can be used to make concrete, and the concrete walls of the tunnel would be made permeable below the roadbed. The structure mentioned above was used in the first Satsuma Tunnel (0.881 km long), the second Satsuma Tunnel (0.339 km long), and the third Satsuma Tunnel (1.150 km long) of JR Kyushu between Sendai and Kagoshima Chuo on the Kyushu Shinkansen line. All three tunnels were dug below the groundwater level, which is naturally rich in spring water. In addition, since the tunnels pass through a Shirasu plateau, which is fragile to water, it was expected that particles of Shirasu soil would be spewed onto the tracks along with the spring water due to the vibration caused by the passing trains. Therefore, the spring water was allowed to seep into the roadbed to prevent it from spewing out onto the tracks.

The structure of the permeable roadbed used in the first and third Satsuma tunnels of the Kyushu Shinkansen. The spring water in the granulated slag is discharged from the tunnel to the entrance.[...]

In the first through third Satsuma tunnels, granulated slag was spread over a width of about 8.6 meters and a thickness of about 1.6 meters. Even at this scale, it was not enough to soak up all of the spring water in the tunnel, which was discharged through the tunnel to the entrance. Therefore, the idea of treating all the spring water with granulated slag may be too far-fetched. However, since the South Alps Tunnel will have a conduit tunnel, and the amount of water flowing into the inlets and outlets at both ends will probably decrease, it may be possible to cope with this problem by increasing the thickness of the granulated slag to, for example, 3 or 5 meters, or if that is not enough, to 10 meters.

Since granulated slag is not a very strong material, the question naturally arises as to whether it can support the railroad tracks. Therefore, I would like to propose a method of driving long piles into the roadbed in the South Alps Tunnel and building the tracks on top of them.

This method was actually used in JR East's 2.965 km long Shirasaka Tunnel between Nasushiobara and Shin-Shirakawa on the Tohoku Shinkansen line. The tunnel's tracks were originally laid on a roadbed, but vibrations caused by passing trains caused the concrete roadbed to collapse, resulting in muddy water mixed with spring water in the tunnel overflowing onto the tracks. While the construction of a conduit tunnel was considered, the problem was solved by building a bridge from 2001 to 2005, effectively supporting the tracks with piles. For the construction, JR East drove 4756 piles into the Shirasaka Tunnel. Since the length of the Minami-Alps Tunnel is 8.4 times longer than that, nearly 40,000 piles would be required if the entire section were to be constructed.

Naturally, JR Tokai would not like this kind of construction. However, if the amount of spring water in the Minami-Alps Tunnel or how much of the spring water flows into the Oi River is not known, I think it would be less troublesome to return the spring water to the mountain instead of trying to find out.

Besides, if the volume of water flowing down the Oi River is lower than expected after the completion of the South Alps Tunnel, JR Tokai will have to do additional work. If this is the case, it would be more beneficial to change the structure of the roadbed of the Minami-Alps Tunnel.

There are many problems with this idea. Not only would the construction cost increase, but the amount of soil that would have to be excavated to build the tunnel would also increase. The vast majority of the soil generated by digging the Minami-Alps Tunnel would be disposed of by building an embankment at Tsubakurosawa, about 4 km upstream from Sawarajima. The current size of the embankment is about 600 meters long, 300 meters wide, and 70 meters high, which is 60 to 70 times larger than the embankment that collapsed in a mudslide in July 2021 at Izuyama, Atami City, also in Shizuoka Prefecture. Therefore, if they dug down to the bottom of the roadbed, further expansion is certain.

Nevertheless, the problem can be solved if Shizuoka City, where Tsubamezawa is located, and Shizuoka Prefecture strictly supervise the construction of the embankment. At the risk of sounding trite, the two parties must work together at some point to complete the Minami-Alps Tunnel.

Reference: Wen Murakami, "Cavities under Tunnel Tracks," in Wen Murakami, Osamu Murata, Shinichi Yoshino, Makoto Shimamura, Masaki Seki, Tetsuro Nishida, Yoshihiro Nishimaki, and Tetsushi Koga (eds.), Protecting from Disaster, Learning from Disaster: The Struggles of the Railway Civil Engineering Maintenance Department, Japan Railway Facilities Association, 2006. December, P216-P218)